An Introduction to Modern Computational Physics#

Physics 246, Spring 2026

Thursday 4:00-5:50pm CST

Room: Loomis 276

2 credit hours

Course Texts: This one!

Welcome! In this course, you are going to learn how to use computation to do amazing simulations: compute how general relativity changes the orbit of Mercury; simulate turbulence; compute the effect of predator and preys on an ecosystem; run a quantum algorithm; and more! We’ve searched and distilled from the world some of the coolest physics we know for you to learn to simulate. Our primary goal in this class will be to help you make these simulations.

Course Logistics#

Lectures: Thursday 4:00-5:50, 276 Loomis

Professor: Lucas Wagner

email: lkwagner@illinois.edu

Office Hours: 3-4 on Wednesdays, 2131 Engineering Science Building

TA(s):

Will Huie

email: whuie2@illinois.edu

Office Hours: 11:30-12:30 on Tuesdays, Loomis 271

Jia Wang

email: jiawang5@illinois.edu

Office Hours: 1-2 Fridays, Loomis 390T

Online Tools#

Google Colab: On Google Colab you will be able to program your code in a jupyter notebook and submit it for us to grade. Please sign in to your Illinois account. You can load things in google colab just by clicking on the relevant button in the notebook (looks like a shuttle). You must then save to your google drive and it will be there later when you go to google colab!

Gradescope: You will submit your projcts via Gradescope, which will also contain your grades and your returned assignments. You will have 2 separate submissionts per assignment, that includes a printout of your Colab document in .pdf format and your original .ipynb. Both submissions are required for each project to obtain credit. Specific instructures with screenshots can be found on the slides from Lecture 1

Calendar#

(These are the dates that we work on the assignment in class; the assignments are due one week later at 3:59 – right before class starts )

Date |

Assignment |

Quiz |

|---|---|---|

Jan 22 |

N Ways to Measure PI Lecture 1 |

|

Jan 29 |

Dynamics Lecture 2 |

|

Feb 5 |

Orbital Dynamics Lecture 3 |

|

Feb 12 |

Exoplanets Lecture 4 |

|

Feb 19 |

Chaos Lecture 5 |

|

Feb 26 |

Particle Physics Lecture 6 |

|

Mar 5 |

Classifying Galaxies Lecture 7 |

|

Mar 12 |

Random Walks Lecture 8 |

|

Mar 19 |

No class! Spring Break |

|

Mar 26 |

Markov Chains Lecture 9 |

|

Apr 2 |

Predator-Prey Lecture 10 |

|

Apr 9 |

Climate Dynamics Lecture 11 |

|

Apr 16 |

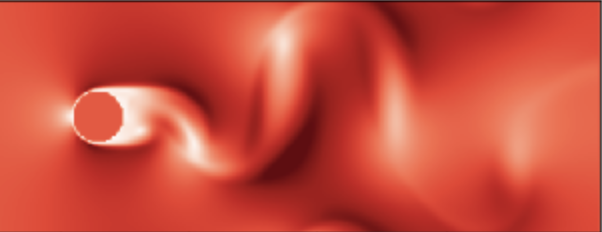

Fluid Dynamics Lecture 12 |

|

Apr 23 |

Quantum Computing Lecture 13 |

|

Apr 30 |

Building a Physical Qbit Lecture 14 |

Coursework#

Computational Assignments#

Criteria The heart of this course will be a series of computational assignments. You will work on the assignments both during class and as homework. Homework will be graded on the following criteria:

70% Functionality

The correct answer is obtained: graphs, code

All questions are answered and correctly answered.

10% Documented code

Well-named variables

Function arguments are documented

10% Code cleanliness

Junk code is removed – we don’t need to know about your side quests!

Functions are functions – that is, they don’t depend on global variables to be set to change their behavior. See below for an example.

10% Plot quality

labelled axes, colors visible, lines distinguishable, range set correctly

For futher resources, see Data Visualization using Matplotlib (and the links within).

Submission You must BOTH share your code (see below) AND turn in the PDF on time into Gradescope. If we only have one or not the other, we will not grade your assignment (and it will be counted late if the other part is turned in after the due date).

Due dates Each assignment is due at the beginning of the next class unless otherwise noted. Extensions may possibly be granted under extreme situations, please email all course instructors together. We will then respond if the extension has been granted. Include the following information:

broadly why you need the extension (illness, family emergency, etc)

when you will be able to submit the assignment by (this should be the new official due date if the extension is granted.)

Other notes

Solutions to the homeworks will not be given.

Partial credit may be applied but will be limited.

AI and collaboration. You may collaborate on assignments but must submit your own work. Related to above, you may not use generative AI, LLM’s, etc to generate code. You must turn this off in google colab.

Some coding advice#

A common issue people often run into is the overuse of global variables. For example, let’s suppose you did this: (don’t do this)

x=5

y=6

def f():

return x+y

z1 = f()

x=6

z2 = f()

In this case, it is very unclear to anyone reading the code what variables f reads in, and it’s very easy for bugs to appear. Combined with the out of order execution of a notebook, this kind of pattern can lead to quite hard-to-find bugs.

Instead do this:

def f(x,y):

return x+y

z1 = f(x=5,y=6)

z2 = f(x=6,y=6)

Instructions for submitting your assignments#

Once you are finished working on an assignment, save a .pdf printout copy of your Colab document. This can be done by the following code

# Get the filename

from requests import get

from socket import gethostname, gethostbyname

ip = gethostbyname(gethostname())

filename = get(f"http://{ip}:9000/api/sessions").json()[0]['name']

filename = filename.replace("%20"," ")

print("CHECK FILENAME", filename)

# Now we mount the file on Drive and convert it to HTML

from google.colab import files

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive')

filepath = "/content/drive/MyDrive/Colab Notebooks/" + filename

!cp "$filepath" ./

!jupyter nbconvert --to HTML "$filename"

files.download(filename.replace("ipynb","html"))

where you replace your filenames above with the appropriate ones for your assignment. Then open the HTML file in your web browser and print from there.

Assignments are submitted via Gradescope, which requires two simple steps.

Download your ipynb file and submit it to the ipynb assignment; it’s just a file upload.

Upload your printout .pdf file into the “… (PDF file)” section and then submit that assignment. Make sure to correctly indicate the question numbers.

We will review both the printout and Colab code while grading your assignment.

Quizzes#

These will be on paper at the beginning of each class (barring the first one), and you will submit them on gradescope. They will just be a few short questions and should only take 10 minutes to do. They are not meant to be stress-inducing; they will simply be simple questions that should be pretty obvious if you’ve done the homework properly.

Final Project (20% of the grade)#

During the final period, you will put together a project that demonstrates something in computational physics. It can be an extension of some of the work that you did in class or something new. This project can be done in small groups (2-4 people). Projects have to be approved by course staff. For your project you will submit a jupyter notebook (in the spirit of what you’ve done in class but expository) as well as give a 5 minute presentation during the finals period for the course.

Extra Credit#

There will be occassional opportunities to get extra credit. These opportunities exist because they are cool and useful for understanding computational physics but too long to fit in the 2 credit hours of the course.

Extra credit assignments will often be described poorly (maybe even something like, `get a full solar system simulation working’). If you have questions about it, please ask before you spend too much time on it. Also, we have no obligation to make extra credit typo-free. Please try to answer the question we mean to be asking.

For the extra credit, per exercise, the grading is all or nothing. We aren’t going to hunt for typos and give partial credit for sort-of working code. The amount of extra credit is listed on the assignment.

Grading#

Computational Assignments: 60%

Quizzes: 20%

Final Project: 20%

Your final numerical score is computed as 100 x (0.80 x (Homework Points + Extra Credit Ponts)/(Total Homework Points) + 0.20 x Final)

The final breakdown of how your grade depends on your numerical score goes as:

100+: A+

93-100: A

90-93: A-

88-90: B+

83-88: B

80-83: B-

78-80: C+

73-78: C

70-73: C-

60-70: D

<60: F

Scores are inclusive of the bottom number - i.e. a 90 gets an A not a B+. All problem sets count for the same amount. Unless otherwise noted, every exercise in a problem set counts an equal fraction of the assignment and every part (a,b,c,…) of an exercise counts as an equal fraction of the exercise. 5 points of the problem set will be for mandatory questions (e.g. time spent on assignment, references, collaborators).

Sometimes there are typos in the assignment (although we are working hard to remove them). Please ask when confused! Don’t spin your wheels a long time on something that might be a typo. These aren’t trick questions - we are trying to ask reasonable things.

Policies#

Attendance#

Students are strongly encouraged to attend class, participate in lectures, and make use of office hours. A quiz will be given every class at the beginning, and can only be taken in class. The first half of class includes a lecture/overview of the problem. The second half of class provides you with time to work on the problem (in small groups and with the instructor and TAs available for help). The first half of class is invaluable to introduce the problem, the second half can help you get started.

If a major event occurs e.g. death in the family, major illness etc, it is best

About using code you find on the web#

The quickest way to deal with the arcana of programing is to ask Google for examples of what you are seeking to accomplish. But you will need to use your judgment in doing this: the Google search “how do I use color maps in python?” is fine, while “show me a script that calculates pi” is not. And you should always credit the original source of code that you paste into your own programs in a comment that includes the URL for the original code. If an author says that his/her code is not to be copied or incorporated into your programs, then DON’T.

The goal of this course is for you to deeply understand this material. For this to work, you’ll need to write your own code.

About Large Language Models#

In a similar vein, you aren’t allowed to use LLM to write your code. This includes chatGPT, google bard/gemini, claude, etc. You must turn off the generative AI in colab if you have it on (which it might be by default).

Academic Integrity#

You must never submit the work of someone else as your own. We understand that many of you will find it helpful to work with other students to master Physics 246. But when you collaborate with your study group on homework assignments, you must be a full, active participant in developing the solutions that you submit for credit.

It is cheating to receive answers from another student and then use them as your own. It is cheating to submit as your own work solutions that you find by searching on the worldwide web (though see “About using code you find on the web”) It is cheating—and a violation of U.S. copyright law—to give (or sell) course material to someone else who intends to redistribute and/or sell it.

All activities in this course are subject to the Academic Integrity rules as described in Article 1, Part 4, Academic Integrity, of the Student Code.

Late policy#

In general, we will apply a 10% penalty for every day that the homework is late. If you need a little more time and have a qualifying reason (i.e., medical, etc), let us know and propose a new due date BEFORE the due date of the homework. If this is approved, you will not be penalized for the late submission.

Useful Python#

Intro Python Jupyter Notebooks:

Why this course?#

As the needs of our students evolve—there is, for example, increasing focus on early readiness for research—the Physics faculty are obliged to adjust both what we teach, and how we teach.

There is a rich tradition of innovation in engineering pedagogy at Illinois. Fifty years ago UIUC became the first school to teach its undergraduates to design computers. More recently, our colleagues have become national leaders in successful efforts to improve instructional outcomes in elementary physics. We intend to continue this Illinois tradition by incorporating computational literacy into the set of core competencies to be mastered by our students.

Just as we require physics majors to enroll in courses taught by Mathematics, but teach the applications of mathematics to physics in our own courses, we hope to do the same with programming. We will continue to require that our students take an introductory course in Computer Science, while incorporating into our own courses machine-based approaches to problems that cannot be solved analytically. Examples include chaos and nonlinear phenomena; fluid dynamics; real-world electrodynamics; quantum mechanics of multi-electron atoms.

This course is a first step. From it, we expect that students will come away with a better grasp of complex phenomena and will be prepared to engage with research experiences that would otherwise have been inaccessible. This will bring to the department’s scientific efforts the collateral benefit of an enlarged pool of competent research assistants. If we are successful, our methods should generalize to other disciplines in science and engineering.

Background: The technical foundation for physics majors includes material in physics, mathematics, computer science, and chemistry. But though the courses taught outside the Physics Department provide an excellent introduction to important subjects, they are insufficiently dense in application to specific physics topics to stand on their own. We find this to be especially true in mathematics and computer science. Consequently, the Physics Department offers undergraduate and graduate courses on mathematical methods for physics, as well as a graduate course in computation.

Recently we have now added two new undergraduate courses in computational physics: this course and 446. By simulating physical systems and observing their (simulated) behaviors, students can more efficiently grasp concepts that might be otherwise obscured by mathematical equations. By developing their computational skills, students are better prepared to assist in data acquisition and analysis tasks in a research setting. In addition, about half of our graduating majors choose employment over graduate study; they often report that prospective employers are seeking to hire employees with computational skills.

Acknowledgements#

The current version of this course is developed by Bryan Clark with updates (including the development of all the slides) by Lucas Wagner and Jaki Noronha-Hostler. An earlier version of this course was developed and run by George Gollin and this current version has non-trival overlapping units and problems. The classifying galaxy assignment closely follows a tutorial at the Galaxy Zoo. The fluid dynamics assignment was originally inspired to get you to develop lattice Boltzmann code similar to that from flowkit.com. The jupyter-ization of the course was done by Ryan Levy and Bryan Clark.